"Kashmir is an experimental laboratory. There is invisible censorship; unprecedented level of fear"

'Kashmir Times' editor Anuradha Bhasin on the attempts to browbeat the media

The media in Kashmir has been gagged before but there was a process. Today, there is utter lawlessness with no accountability. There is invisible censorship; it is not announced or seen, but it is felt. In these last 14 months, there is an unprecedented level of sense of fear. The entire media fraternity that is daring to speak is under threat, constant threat. Media has lost its sense of confidence.

So says Anuradha Bhasin Jamwal, the Executive Editor of Kashmir’s oldest English newspaper Kashmir Times, on the journalism podcast, J-POD.

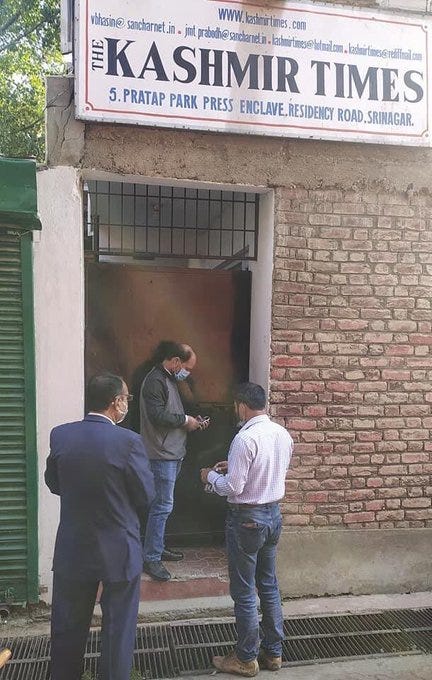

Last year, Anuradha Bhasin went to the Supreme Court questioning the lockdown in Kashmir after the state’s special status was revoked. In the last 15 days she has paid the price. On October 4, she was evicted from her government-allotted flat in Jammu; on October 19, Kashmir Times was evicted from its government-allotted office in Srinagar.

“Today’s challenge is the worst of my journalistic career,” she says. “My Hindu identity is a privilege in today’s India because if I was a Kashmiri Muslim, I would have been targeted much more.”

The ‘V’ word—vendetta—has been used.

“In the 1990s, there were ways of censoring media. Distribution would be stopped, advertising would be withdrawn, bans would be imposed by both militants and the government. But even at that time, at the end of the day, there were greater expectations from the government, not from non-state actors.

“At that time, there was confidence that you could still take recourse to remedial measures, you could go to the courts, you could approach people in the government at the higher level. You could pick up the phone and ask the governor what was happening. There was a level of accountability in the government. The institutions were working.

“This time, we are facing a new wave of censorship, a different kind of censorship, it’s a more invisible censorship. It’s not said, it’s not announced, it is felt. There are minimal ways in which you can take recourse to remedies. There is no accountability. You can keep asking questions, but they don’t respond, as if you don’t exist,” says Anuradha Bhasin.

Listen to the full podcast with Anuradha Bhasin

Complete lawlessness

“This is not the first time we faced persecution at the hands of the government. In 2009, the government was unhappy with what we were writing. They ordered the demolition of an extension to our building. There was a proper order. There was a method in place even though it was attempts to censor and gag the press.

“While the government action against Kashmir Times now isn’t surprising, it was shocking the way it happened. You cannot just lock up an office without any notice. There is complete lawlessness to the whole exercise.

“In both my apartment and office, ownership of my belongings has been taken of my organisation. Under what law? The whole idea is to scare me, intimidate me, so that I cannot focus on what I want to speak and say.”

Orders from above

“They can lock up a building, you can put a pad lock, but you cannot lock up voices, you cannot lock up ideas. They are going to emerge. The more they beat us, the stronger we emerge.

“There was somebody much higher than the estates department behind the eviction decision. The flip-flops and lack of preparedness shows that it was something coming from the top, from somewhere higher up.

“Media has been walking the razor’s edge for a long time in Kashmir, particularly in the last 30 years of the armed conflict, caught between the two guns, the security forces and the militant groups. Earlier journalists would come together and speak up for each other. In these last 14 months, there is an unprecedented level of sense of fear. Media has lost its sense of confidence.”

Sophisticated arm-twisting

“When I went to the Supreme Court, the very next day the state government stopped government ads to Kashmir Times. There was sophisticated arm-twisting to browbeat us. There were malicious campaign against me. And then these evictions. They are an attempt to silence us, to forbid us from resuming out print edition.

“The government does not want any kind of independent voice. I was aware that if I would speak, there would be consequences. There were only two choices for me, either I surrender or speak out. I am unwilling to bow down, and I am unwilling to be silenced. I am not stopping.

“There is a media policy that the government has come up with. No rules are framed. It is a stringent piece of legislation that seems straight from an Orwellian world, which disallows anybody to say anything, there is no system of accountability. Any word could be construed as fake news or anti-national, and you could face criminal cases.

Kashmir media lab

“Kashmir is an experimental laboratory for everything in the rest of the country today. Even six months back, Kashmir stood out in terms of the persecution of journalists, the threats and fear to their lives. But today when you look at various other parts of the country, like Uttar Pradesh and Jharkhand, the difference has been obliterated.

“It’s important to save your organisations, save your platforms, but more important is to save your voice. If you have your voice, the platforms will come back to you. If your entire energy is focused on saving the platform at the cost of killing journalism, at the cost of information, at the cost of killing the truth, I think we are on the wrong path.”

Also read: Hell for reporters, photogs in paradise

How journalists are getting their stories out from Kashmir

No newspapers for three days and no one is bothered

Strict orders not to give curfew passes to local journalists