Everything you need to know about the India-China face-off in 11 tweets---and 33 links

And how Rahul Kanwal got a crash course in "Cassandra"

Twenty-four hours is a blink of the eye when you ride the news cycle, downhill.

On Monday, Indian media was being accused of excess—of going overboard, of being intrusive, insensitive, voyeuristic and worse, in its coverage of the death of the young actor, Sushant Singh Rajput.

On Tuesday, as news of Indian casualties during the “de-escalation” in the face-off with China at the Line of Actual Control became known, it was being hauled over the coals for the exact opposite reasons.

For doing too little, for not digging deep, for being too deferential to its master’s voice.

The deadly conflagration, the first in 45 years with fatalities (and on the third anniversary of the Doklam imbroglio) had been simmering for over a month, but deftly underplayed, denied, gaslit, lied and spun out of the public eye.

But when the Army officially issued a statement at 12.52 pm (and then amended it 16 minutes later), there was no where to hide.

And as it became clear that the casualty count was “significantly higher” than a colonel and two jawans—and that a major and a captain were still in PLA custody—it was clear that a “watershed moment” had been reached.

How did they die? Some say they were hit by stones; probably beaten to death; some say they slipped and fell during pushing and shoving.

Why did they die? The People’s Liberation Army accuses India of going back on its word arrived at on June 6.

Lt Gen H.S. Panag, one of the few voices in the media to stick his neck out, called it for what it was: the ‘Kongka La’ moment, a throwback to an incident in 1959 leading up to 1962, when India last met China on the battlefield.

Ananth Krishnan, The Hindu’s Mandarin-speaking former Beijing correspondent, pointed out the obvious.

Nirupama Subramanian, resident editor of The Indian Express in Mumbai, put it in wider context.

The parallels were quickly drawn: Kargil during the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government, now this during Narendra Modi’s, with a foreign minister (S. Jaishankar) who had served in Beijing as India’s ambassador.

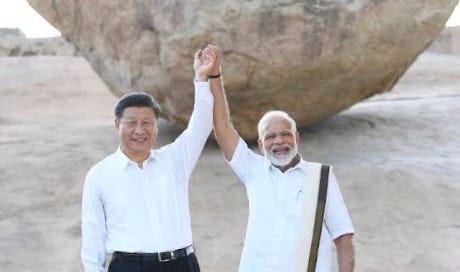

And despite excessive Modi’s outreach to China, as noted by Congress leader Ahmed Patel a couple of days ago.

The news kicked off the usual spat between journalists in India, for many of whom ideology has replaced idealism as the calling card, and with journalists in China.

There was minor jubilation when, at 1.54 pm, Wang Wenwen, the chief reporter and opinion writer of the official Global Times newspaper, said there had been Chinese casualties too. She was quickly wired up into TV studios.

At 2.37 pm, the paper’s editor Hu Xijin too confirmed the news but with a veiled warning. By day’s end, the paper was prompted to issue a formal clarification.

The buzz over Chinese casualties was just what nationalist media were looking for, till Wang Wenwen clarified she was only quoting from an unheard-of Indian news outlet. In other words, Indian media outlets were quoting a Chinese journalist citing an Indian outlet on Chinese fatalities.

“Something exceptionally silly,” said Praveen Swami, group consulting editor of Network 18.

The unfortunate loss of lives in the escalation during the “de-escalation” was validation of the journalism of Ajai Shukla of Business Standard, and Manu Pubby of The Economic Times, who for days had been contesting the sarkari version that things were back to status quo ante.

Manu Pubby tweeted the story he had done on May 12 with Rahul Tripathi.

But in the true tradition of the social media age, 16 June 2020 turned out to be the day to educate media folk about journalism and history after Rahul Kanwal of India Today TV alleged:

“There’s a bunch of Cassandras who are delighted that the Modi Government is on the back foot with China.”

It was an odd position for Kanwal, son of an Army man, to take, especially given that he himself had played the role before.

Cassandra, reminded Raghu Karnad and Prem Panicker sagely, “warned her arrogant rulers, again and again, about true dangers to their city; was disregarded and abused and told to be silent, but was always right.”

And as Hindi-Chini-bye-bye loomed, an old ghost popped in to say hello.